IIT-Madras: Indian Institute of Innovation

With incubators for deep tech startups, funding for students and support for corporate R&D, the institute is fostering an entire ecosystem of cutting-edge ideas

IIT-Madras’s focus on core technology has attracted entrepreneurs in droves

IIT-Madras’s focus on core technology has attracted entrepreneurs in droves

Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes India The incubation cell on the third floor of the IIT-Madras Research Park is an epicentre of nervous energy. The glass door is flung open every few minutes as entrepreneurs, fresh out of brainstorming sessions with their mentors, storm to their workstations to put the learnings to test. Some are building energy-efficient batteries and smart farming technologies while others are putting together remotely-operated vehicles that would deep dive into oceans to facilitate underwater inspections.

But what a majority of the startups at the incubator have in common is they are the so-called deep tech startups, that are heavily reliant on science and technology—artificial intelligence, virtual and augmented reality, computer vision and robotics—and are seldom consumer-focussed, a sharp contrast to investors’ favourites such as online retail, payments or ride-hailing companies.

The incubation cell’s single-minded focus on such businesses, which may struggle to find a footing elsewhere be it for lack of investors or experts to handhold them, has attracted founders by the droves. This, despite the facilities being housed in Chennai, about 350 km from Bangalore, India’s Silicon Valley and startup hub. “All the entrepreneurs here are core technology people who speak the same language and understand issues that impact technology-focussed ventures. Exchange of ideas becomes even easier with people on the same wavelength,” says Ankit Poddar, chief executive at Swadha Energies, which develops power saving technologies.

Tamaswati Ghosh, chief executive at the incubation cell, says the only motive of the incubators at the institute—apart from this nodal incubation cell set up in 2013, there are three others focussed on social impact, biotechnology, and healthcare and medical technology—is to nurture innovators, not make money. At the same time, they prepare the startups to survive an unforgiving world outside. “Our seed funding support ranges from ₹5 lakh to ₹50 lakh, which is typically disbursed in tranches, based on milestones. The initial ₹5 lakh is a grant and funding beyond that is given as a soft loan at 6-8 percent annual interest. Minor equity is taken for overall incubation support, with emphasis on mentoring—technical, compliance and business—and access to a host of services,” says Ghosh. “The startups have to demonstrate they can absorb a loan and pay us back with interest. Founders are also made aware and trained early on about what it takes to be investment ready.”

Take for instance Sabarinath Nair’s maiden venture, Skillveri Training Solutions, a startup that develops simulators for vocational courses such as painting and welding. A former marketing professional, Nair quit his job to set up the firm in March 2012, hoping the products will be lapped up by corporates and training institutes.

But that was not to be. Skillveri, which found a home at the rural technology and business incubator after being snubbed by two Bengaluru-based incubators, fell woefully short of revenue targets after the first year of operations. “In the very first business plan I prepared, I had projected ₹8 crore but made only ₹7,500. I had no money to pay salaries to my six employees,” recalls Nair. He couldn’t fathom a better way to pull his company out of the quagmire than ask the incubator for a loan.

“Initially, they refused,” says Nair. Instead, he got some pearls of wisdom from mentors, which Nair claims to follow to the T even now. “They identified that we were not being smart at sales and identifying the right customers. We were doing a demo for anybody who showed an interest in the product without realising many of them were calling us for an academic interest,” says Nair. “We got a loan only after we made the business more efficient.”

Today, Skillveri counts Ashok Leyland and the Tata Motors passenger car division as its clients. The company has got ₹8 crore in funding from Ankur Capital and Michael and Susan Dell Foundation and is gunning for ₹8 crore in revenues this fiscal, four times the turnover in 2017-18.

BUCKING THE TREND

Skillveri is among a burgeoning crop of protégés to have attracted institutional investors, along with Tiger Global Management-backed electric scooter startup Ather Energy, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation-backed underwater robotics startup Planys Technologies, Cisco chairman John Chambers and IDG Ventures-backed speech recognition startup Uniphore, dairy technology startup Stellapps that is backed by Blume Ventures and deep learning startup HyperVerge that is backed by New Enterprise Associates.

At IIT-Madras, such startups are a norm rather than an exception, which makes the incubation cell an oddity among peers. While India is home to at least 100 incubators and accelerators, not many have consistently nurtured deep tech startups. A few exceptions, such as Axilor Ventures backed by Infosys founders Kris Gopalakrishnan (also an IIT-Madras alumnus), SD Shibulal and Srinath Batni, and Avishkar, an initiative of the International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, are only a couple of years old. Even investments into deep tech or hardware product companies by venture capital firms have been sporadic. While there are funds like Pi Ventures and Endiya Partners, they are few and far between.  The incubation cell also prepares startups to survive in the world, says CEO Tamaswati Ghosh

The incubation cell also prepares startups to survive in the world, says CEO Tamaswati Ghosh

Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes India “Most deep tech companies are stuck in the prototyping stage, figuring out an application for their research. To form a venture capital fundable company, the prototype needs to be productised into something that can be built at scale with the right economics,” says Rutvik Doshi, managing director at Inventus Capital Partners. “Also, there isn’t any concerted effort from funds to back such companies because generic funds are struggling to clock returns from their early investments. Businesses in India take at least seven years to mature and deep tech companies could take even longer, which makes them inherently riskier.”

The startups at IIT-Madras have bucked the trend, thanks to a group of illustrious alumni who not only pull them out of the vortex by cutting the first cheques, but are also donors to the incubator’s ₹5-crore annual corpus. Junglee founders Anand Rajaram and Venky Harinarayan (1993 and 1988 batch alumni respectively), senior Google executive Prasad Setty (1992 batch) and Swaroop Kolluri, 1986 batch alumnus and founder of Neotribe Technologies are among the backers of the incubation cell.

Ghosh says 34 of the 150 startups incubated at IIT-Madras have raised ₹750 crore in investments, while 20 have shut shop. The incubation cell has so far made a windfall on two investments—nanotechnology-based water purification startup InnoNano Research, a venture by an institute professor T Pradeep that was bought by NanoHoldings LLC in 2016 for $18 million, and Rope Enterprises, where the incubator sold its stake to an undisclosed investor earlier this year.

STUDENTS AND BEYOND

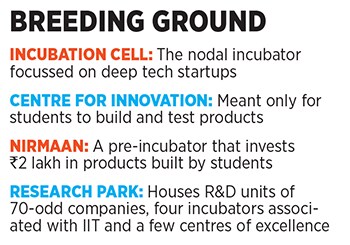

The IIT-Madras campus, a 250-acre lush expanse where deer can be spotted aplenty, has also quietly emerged as a breeding ground for aspiring entrepreneurs right from their student days. Leading the charge is the Centre for Innovation, a place for students to toy with ideas and products. Many of the well-known alumni of the incubation cell—Ather, Planys, DeTect Technologies, HyperVerge, NeoMotion, Aibono and Lema Labs, among others—started as projects at the centre. In fact, about 40 percent of the startups to have been housed at the incubation cell were founded by an IIT-Madras alumnus.

Indeed, an ecosystem is being built at the Research Park, which is now home to four incubators, startups and about 70-odd corporates who have chosen to house their R&D centres at the facility, about a couple of kilometres from the IIT-Madras campus. Here, the corporates can access a wide pool of academics at IIT-Madras, apart from gaining exposure to some cutting-edge work by startups. The academics on campus—professors, researchers and students—find in those corporates an avenue to test business cases for their innovations, making it a perfect example of industry-academia collaboration.

The facility, a brainchild of Ashok Jhunjhunwala, a professor at the department of electrical engineering currently on a sabbatical from the institute to serve as principal advisor to railways minister Piyush Goyal, boasts of a clientele including Saint-Gobain, Tata Consultancy Services, Titan, Amada Soft, Cognizant, Ashok Leyland, BHEL and the DRDO. “The idea was to put three sets of people together, who can seek each other out in a formal or informal environment to come up with solutions to all kinds of problems. They are high quality faculty, the industry that knows how to convert an innovation into a commercial product, and youngsters,” says Jhunjhunwala. “Here we look at everything from a business lens. Research and development without keeping business at the forefront does not work.”

Almost half of the faculty at IIT-Madras today works with the industry as against a paltry 10 percent about seven years ago. In the process, the research park has evolved into a cash cow for various stakeholders.

“We have a rental income. The research park has been making profit year after year. We have invested ₹475 crore on the facility, of which ₹100 crore came from the government and the rest is our own money. For the incubation cell, it helps them make money through equity sale. For the IIT, it is an enabler of consultancy money, because whenever an industry works with an IIT faculty, there is a fee involved,” says Jhunjhunwala.

In an attempt to ensure the research park does not end up being a piece of inexpensive real estate for the corporates, the institute has put in place a strict evaluation mechanism. “The scope of work includes collaborative or sponsored projects with IIT-Madras. The companies can also sponsor masters or PhD students. Senior industry executives can also teach at the IIT,” says Ghosh of the incubation cell. The corporates are scored on the basis of their engagement with the institute. If they fail to meet the bare minimum requirement, they are first warned. Then the rentals are increased as a penalty, and last, they are asked to vacate the premises.

Jhunjhunwala does not identify the companies that have been asked to leave but insists such instances are few. In fact, corporates are keener than ever to sponsor research. For instance, the Centre of Battery Engineering, set up in June 2016 to develop battery capabilities for electric vehicles, counts Mahindra & Mahindra, Ashok Leyland, Indian Oil Corporation Ltd and the Essel Group among others as sponsors. The centre acts as an interface between car, battery and charger manufacturers over issues related to the large-scale rollout of electric vehicles in the country. The centre is also on the verge of rolling out a set of batteries aimed at curbing pilferage of electricity.

“We have developed ‘locked smart batteries’ that are programmed in such a way that you will be able to discharge them only with the vehicle with which it is matched. Also, you cannot get it charged at any other place other than the authorised charger. It will be launched in the markets soon,” says Prabhjot Kaur, director.

At IIT-Madras, innovation is lauded. The stakes are high and the deterrents many. But, the likes of Jhunjhunwala, Ghosh, Kaur and Balaraman are determined to keep the flag flying.

First Published: May 04, 2018, 11:09

Subscribe Now